"A blind feeling of one’s own being, stretching unto God..." ~The Cloud of Unknowing

Q. What is contemplation? How is it different from meditation or prayer?

Many of us in the Judeo-Christian tradition are most familiar with prayer, which usually consists of thinking or speaking words to God. Prayers may consist of prayers for ourselves (petitionary prayers, in which we make requests of God) or on behalf of another person, persons, or group of people, or aspect of Creation (intercessory prayers). Prayers may also be expressions of struggle, pain, grief, thanksgiving, gratitude, joy, or other emotions put to words.

Meditation can consist of rumination on a phrase, as in the words of the tax collector in Luke 8:13, “have mercy on me, a sinner”, a single word, like peace, holy, or an image, like the flickering of a candle, or icon, or the breath. The phrase or image is used to center one’s focus. Meditation can be an end in itself, or act as a precursor to contemplation.

Contemplation is wordless presence in the Presence of God. In the Christian contemplative tradition there is a difference between kataphatic and apophatic prayer. “Kataphatic” prayer has content; it uses words, images, symbols, ideas. “Apophatic” prayer is prayer without words, images, and thoughts. It is a practice of resting in the presence of God in silence without words or images, a continuous letting go of thoughts. Centering Prayer is a form of apophatic prayer. Ignatian prayer is mostly kataphatic.

Cynthia Bourgeault, Episcopal priest, teacher and contemplative retreat leader, notes that one of the main differences between Buddhist meditation practice and Christian contemplation is with contemplation one lets go of being the chief acting agent. One allows themselves to be acted upon by Someone or something else. It is a secret embrace initiated from the other side.

Q. How Do I Begin?

Jesuit theologian Walter Burghardt once described contemplation as taking a “long, loving look at the real.” More than anything else, contemplation is a way of being in the world, one that is more expansive and connected. In the Judeo-Christian context, we believe that the desire to be “present in the Presence” of the divine, however named or experienced, is initiated by the Mystery we call God. In this article from the website, www.ignatian spirituality.com, Vanita Hampton explores some of the challenges and blessings a “long, loving look at the real” can evoke.

Simply focusing on the in-breath and out-breath for a period of time is a good place to begin. Breathing techniques, including breath counting, help us to simultaneously slow down, focus on our bodies, and help us become aware of the busyness of our minds. By cultivating an internal sense of an observer, we can begin to create some “distance” among the interplay of thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and sense of self that continually arise within and around us. In the words of Victor Frankl, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

“Breathing in, I calm body and mind.

Breathing out, I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment

I know this is the only moment.

~Thich Nhat Hanh

Q. What does the term “contemplative life” imply?

We all differ in our ability to maintain a focus on the presence of the holy throughout the day and among the seasons of our lives. Other activities in our lives, including the demands that we focus on work or other people, including those we love, usually take precedence. It is easy to fall into the trap of dualism, and label some experiences as being more “spiritual” or contemplative than others. It is more helpful to think of the movement towards maintaining a focus on the holy as a lifelong journey and to express gratitude for those times and durations when “something happens.” Buddhist mindfulness practices can be helpful in relaxing a sense of barrier between some sought-after idealistic spiritual state of being and “normal life.” When we experience glimpses of God or the divine in the midst of life, they remind us both to be grateful and to keep our senses open to future glimpses. “Little becomes much” in a more contemplative life.

Q. What are some different forms of contemplation?

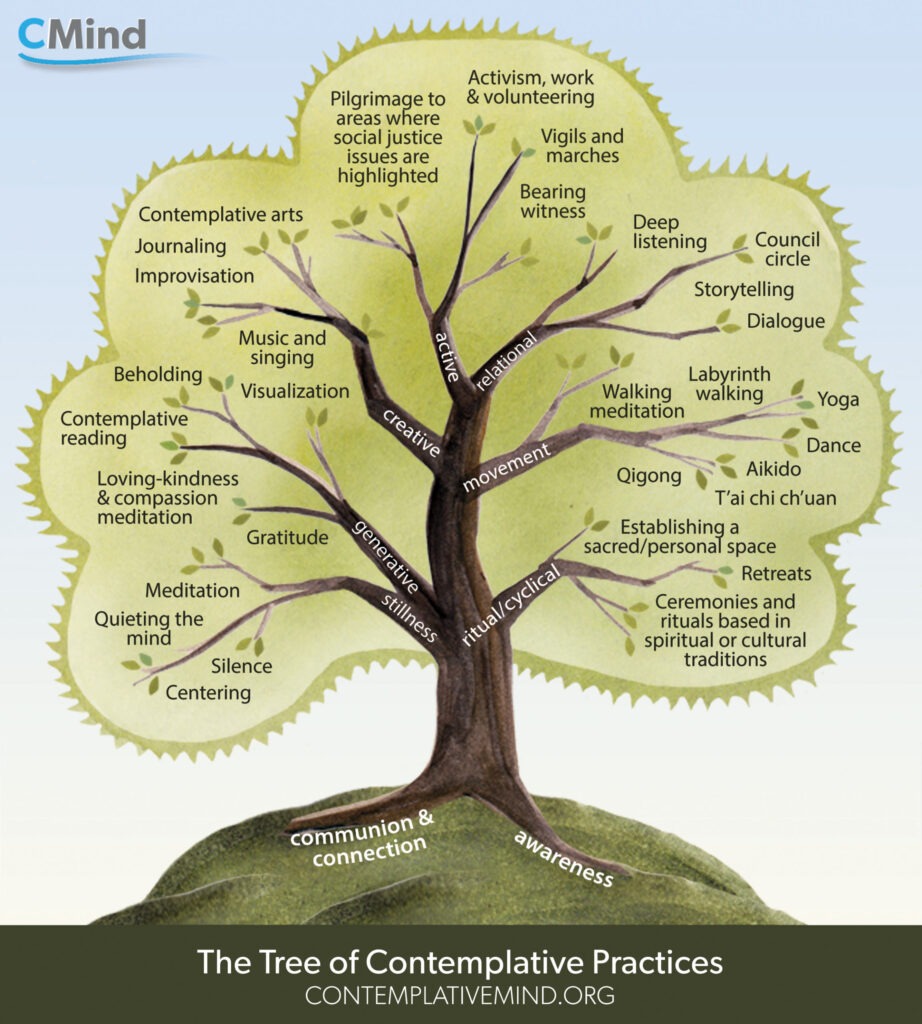

The (now-closed) Center for Contemplative Mind in Society published a Tree of Contemplative Practices which provided a helpful diagram of practices.